Russian Wagner Supporter Convicted – Sabotaged Ukrainian Family’s Car

A Russian-born man with Swedish citizenship has been convicted of slashing the tire of a Ukrainian refugee family’s car and attaching a sticker bearing the symbol of the notorious Wagner Group.

The victim: “It felt like the war had reached here.”

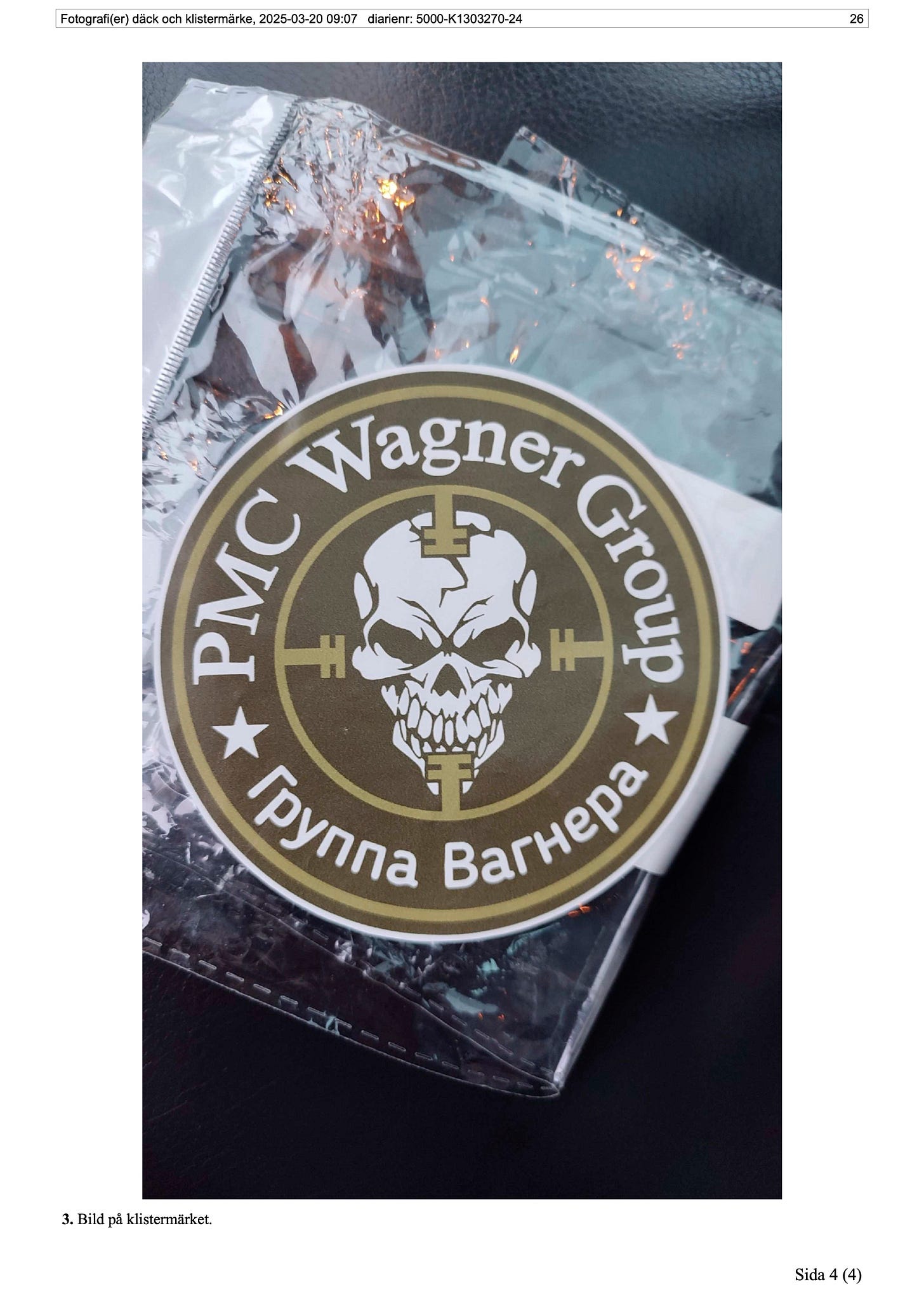

On a Saturday morning in October 2024, a Ukrainian refugee family was shopping at the discount store ÖoB in Kiruna. When they returned to the parking lot, they found a sticker bearing the Wagner Group’s emblem — a skull and Russian text — affixed beneath the car’s headlight.

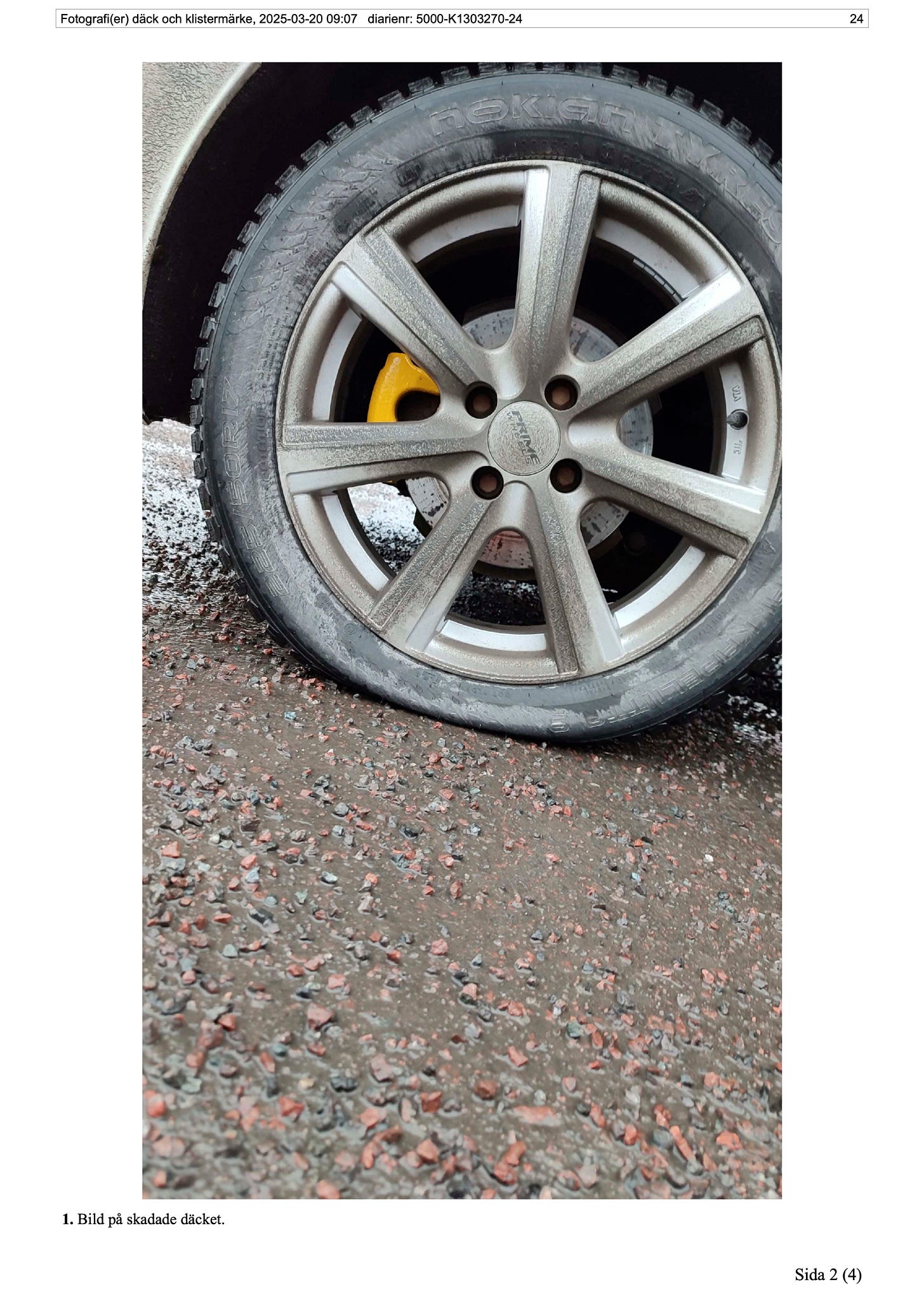

Shortly afterward, they discovered that one of the tires had been punctured. Footage from the car’s built-in camera shows a man approaching the vehicle, bending down by a wheel, and making a quick arm movement. In the audio, a distinct hissing sound can be heard — the air escaping.

“It was awful. I felt threatened and violated. I never thought something like this could happen here,” the man told police during questioning.

In his police interview, the Ukrainian man explained that his family came to Sweden after the war broke out in their home country. He works and tries to live an ordinary life in Kiruna. On the car, he had a sticker from his hometown, Mariupol — something that was used a reason for vandalizing the car.

“I put it there to remind myself of where I come from (Mariupol). It’s my hometown. I never imagined anyone would be offended by it.”

He remembers the incident clearly:

“When we came out of the store, I saw a sticker with the Wagner logo on the car. I recognized the symbol immediately. It’s a Russian military group that has killed people in my country. It felt like a threat.”

The family drove home but soon noticed that one of the tires was losing air. Later, when he watched the footage from the car’s built-in camera, he could see the man bending down and hear the sound of air hissing out.

“He damaged the tire. You can clearly hear it on the recording when it happens. He was alone there.”

He also said that for several weeks after the incident, the family felt uneasy whenever they went out or drove the car: “We no longer felt safe. It was as if the war had reached here.”

Claimed to have seen “Nazi symbols” — but the court didn’t believe him

The defendant, 48-year-old Oleg Vlassov from Kiruna, admitted in court that he had placed the sticker but denied puncturing the tire. He claimed he had seen “neo-Nazi symbols” on the Ukrainian man’s shirt and car, which made him want to “restore balance.”

But neither the police nor the prosecutor found any evidence to support the claims of Nazi symbols. In fact, the car bore a sticker from the Ukrainian city of Mariupol — the family’s hometown — not a far-right emblem.

In its verdict, the Gällivare District Court ruled that Vlassov’s explanation was “highly improbable” and that there was no evidence supporting his claim about Nazi symbols. The court concluded that Vlassov was alone at the car and that the evidence — the video, audio, and photos — all clearly pointed to him.

Who are the Wagner Group?

The Wagner Group is a Russian paramilitary organization founded in 2014 by former GRU officer Dmitry Utkin. Its mercenaries have taken part in armed conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, Sudan, Mali, and the Central African Republic.

The Wagner Group is a Russian paramilitary organization founded in 2014 by former GRU officer Dmitry Utkin. Its mercenaries have taken part in armed conflicts in countries such as Ukraine, Syria, Libya, Sudan, Mali, and the Central African Republic.

Wagner has been accused of severe human rights abuses, including torture, rape, and executions of civilians. In Ukraine, the group has played a prominent role — particularly in the battle for Bakhmut, where thousands are reported to have been killed. There is also documented evidence showing that Wagner has executed its own fighters who attempted to desert.

The UN and several human rights organizations describe Wagner as one of the most brutal military actors in the world. Despite this, Oleg Vlassov called them “brave people” and told police that he would not have sided with Sweden if Russia were to attack.

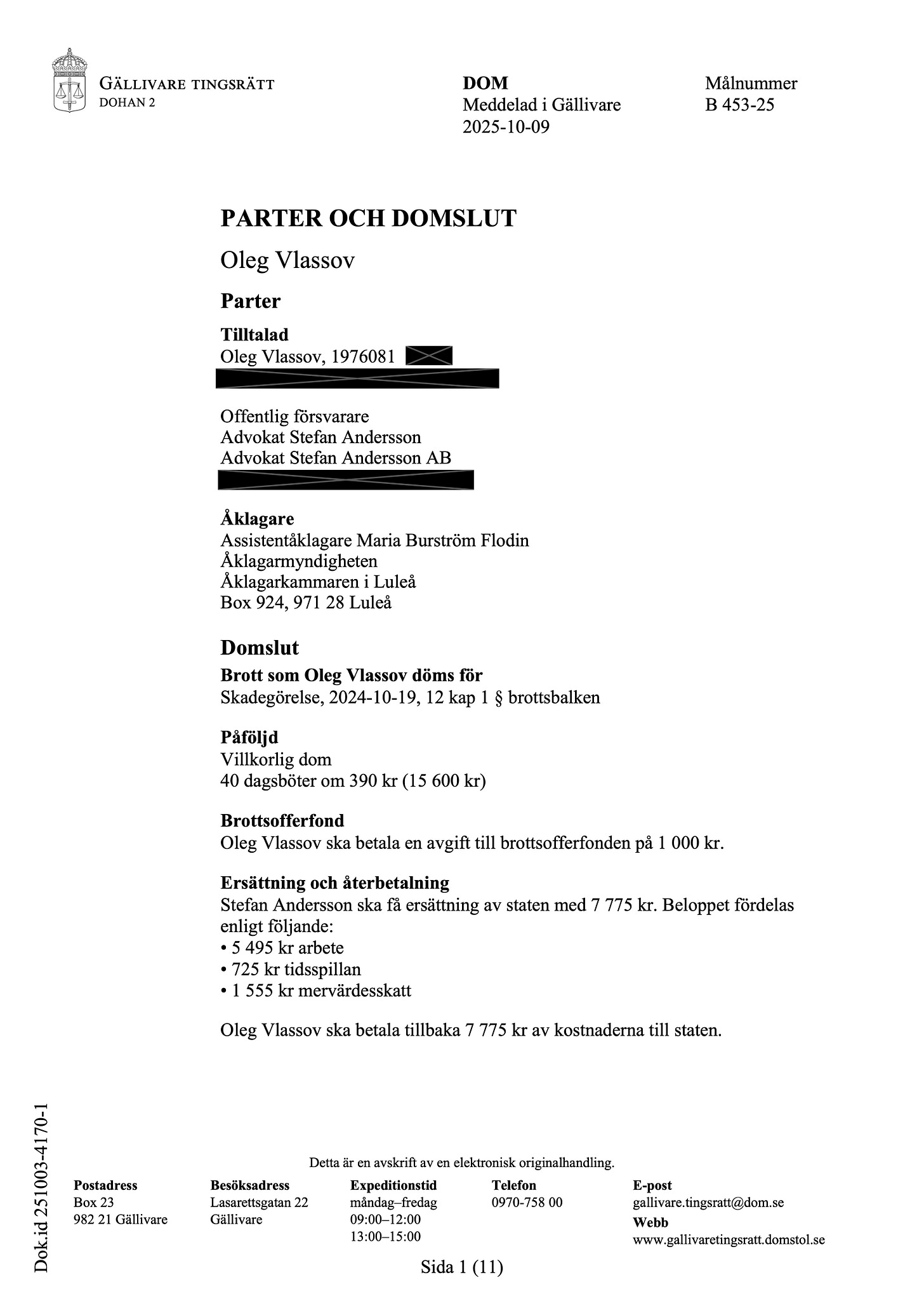

Sentence: Conditional sentence and fines

Vlassov was convicted of property damage of normal severity and sentenced to a conditional sentence along with 40 day-fines of 390 SEK each — a total of 15,600 SEK. He must also pay 1,000 SEK to the Crime Victims Fund and 7,775 SEK in legal costs.

Police initially investigated the incident as a possible hate crime, but since no additional evidence was found during the house search, it was ultimately classified solely as property damage.

Swedish citizens

Oleg Vlassov, 48, claimed upon arriving in Sweden that he was stateless, Russian-speaking, and most recently residing in Estonia. He came to Sweden in the autumn of 2009 and was granted Swedish citizenship in 2017.

He now lives in Kiruna with his family and has two children, born in 2006 and 2017. His wife, who also has Russian origins, moved to Sweden in 2005 and became a Swedish citizen two years before him.

According to the Swedish Prison and Probation Service’s personal investigation, Vlassov lives under stable circumstances with housing, family, and employment. However, the agency assessed that the incident leading to his conviction demonstrated “border-crossing behavior,” even though the risk of reoffending was considered low.

Facts: Russians in Sweden

According to Statistics Sweden (SCB, 2024), around 23,000 people born in Russia are registered residents in Sweden. If including individuals of Russian origin from countries such as Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, and Latvia, the group is estimated to number between 80,000 and 100,000 people.

Sweden has several Russian-language networks, associations, and media outlets. At the same time, concerns are growing about Russian influence and propaganda — particularly through social media and religious channels. The Russian Orthodox Church — subordinate to the Patriarch in Moscow — has drawn special attention from the Swedish Security Service (Säpo), which has warned that the church may be used as a tool for Russian influence and intelligence activities.

The case of the church in Västerås is one example where authorities have voiced concern. According to the Swedish Security Service (Säpo), foreign powers use organizations in Sweden to advance their own interests and sow division — something believed to include parts of the Russian ecclesiastical structure as well.

Christian Peterson

🇸🇪🤝🏻🇺🇦